Studies of how it starts and what could stop it are focus of celiac disease symposium

By Amy Ratner, Medical and Science News Analyst

Scientists delving deeper into celiac disease may find out why it starts by looking at bacteria in the gut. And they may find out how to stop the genetic autoimmune condition by developing drugs that specifically train the immune system into not reacting to harmful gluten.

This growing understanding of the disease stems from increased research that has made substantial progress in the past decade, bringing new treatments closer to reality.

Advances in diagnosis are also being made, including the potential to reduce the amount of time someone on the gluten-free diet would have to eat gluten again from while preparing to be tested for celiac disease.

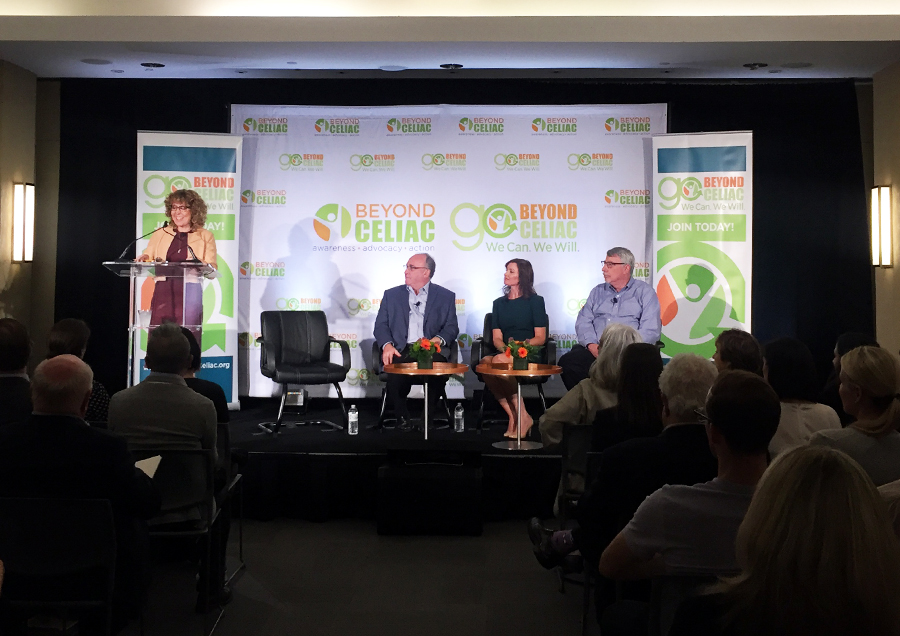

These were among the key points made by celiac disease experts at the Celiac Disease Research Symposium held Wednesday by Beyond Celiac. The symposium, conducted in conjunction with the organization’s 15th anniversary, was designed to bring the latest not only in the field of celiac disease, but also from research into other autoimmune diseases.

“Only through research are we going to be able to improve the quality of life for people in the celiac disease community. And for research to progress, our community needs to be aware, interested and involved,” said Marie Robert, M.D., Beyond Celiac chief scientific officer and symposium moderator.

That community involvement was demonstrated by a live and webcast audience of nearly 2,800 that included all 50 states, Puerto Rico, Washington, D.C. and countries around the world. That’s an increase of 60 percent compared to the symposium audience in 2017.

Stephen Miller, Ph.D., Maureen Leonard, M.D., and Ciaran Kelly, M.D., formed a panel that explored the role of the immune system in celiac disease, groundbreaking research into the gut microbiome, and breakthroughs in clinical trials.

Autoimmune disease

Autoimmune diseases are in the top three disease groups found in the human population, according to Miller, director of the Interdepartmental Immunobiology Center at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

These diseases are now being diagnosed more frequently, which Miller said could be explained by the hygiene hypothesis. This is the theory that people are exposed to less germs early in childhood due to cleaner living conditions.

“When we were all exposed to a lot of microbes early in life that tended to quell the propensity to develop these diseases, said Miller, who is an internationally recognized for his research on pathogenesis and regulation of autoimmune diseases.

Celiac disease, like other autoimmune conditions, is a multifaceted problem, that requires both genetic susceptibility and a trigger, often some type of infection, he noted.

“Development of celiac disease could be a combination of ingesting a gluten-containing meal at the wrong time when you’ve caught an intestinal infection with the wrong kind of bacteria,” Miller said. “That combination on top of your genetic background could contribute.”

T-Cells: White blood cells that function as the body’s disease fighting soldiers and are improperly activated by gluten in those who have celiac disease.

Miller is currently working on an antigen-specific immunotherapy to treat celiac disease. Instead of using an immunosuppressant drug that would dampen the response to gluten but also make patients more susceptible to infections and cancer, this therapy targets only the immunopathic T-cells that cause the reaction to gluten.

Nanoparticle: a very small object with dimensions measured in nanometers that behaves as a whole unit in terms of its transport and properties. Nanoparticles can be made to control and sustain release of a drug and have a variety of potential applications in the biomedical field.

Fragments of the gliadin protein in gluten are encapsulated in a small, biodegradable shell. The shell is made from the same material as absorbable sutures but is shaped into a sphere, called a nanoparticle.

The nanoparticle is administered through an intravenous infusion (IV) and travels to the liver and spleen where particular cells digest it. These cells then present to the immune system in a way that induces regulatory cells that then go back and shut down the harmful reaction to gluten.

The body’s immune system is reprogrammed to tolerate gluten, preventing symptoms and damage to the villi lining the intestine. In celiac disease, the gliadin fragments of gluten pass through the intestinal wall and activate the immune response, causing inflammation and intestinal cell damage. By encapsulating the fragments in nanoparticles and delivering them through the blood stream to the liver and spleen, the immune system can be fooled into accepting gliadin as a normal part of the diet.

“The idea is that if we could induce immunologic tolerance specifically against gluten, we could stop the whole downstream process, including the autoimmune components, taking away the inflammatory stimulus,” Miller explained.

The treatment is in Phase 1 clinical trial and there are many unknowns, but Miller said the hope is that antigen immunotherapy would permanently provide patients with protection would allow a return to a diet containing gluten.

The microbiome

The development of the immune system is influenced by the microbiome, the collection of organisms that live in and on the body.

Leonard, clinical director of the Center for Celiac Research at Treatment at Mass General Hospital for Children, is exploring the microbiome to determine what triggers celiac disease and what might prevent it. The Celiac Disease Genomic, Environmental, Microbiome and Metabolomic Study (CDGEMM) is tracking the gut microbiome of 375 high-risk infants with a parent or sibling diagnosed with celiac disease.

Leonard and other researchers in the United States, Italy and Spain will monitor the children’s data, symptoms, and potential celiac disease onset from birth to age five by collecting blood and stool samples and other information related to celiac disease. The study is looking at the bacteria in the gut and its overall function, according to Leonard. Comparisons between the microbiome of children who develop celiac disease are being compared to the microbiome of those who don’t to determine if the focus of the bacteria is different.

Several children participating in the study have developed celiac disease, enabling researchers to analyze data from both before and after the disease was detected. This is a step towards the study’s goal of identifying a distinct microbial pattern that will allow researchers to predict who will develop celiac disease before it happens.

Leonard said researchers are looking to see if they can identify a shift in the microbiome. “If we can do that before celiac disease develops the hope is that we can … intervene before it happens.”

Celiac disease research

Despite growing understanding among researchers of the microbiome and the autoimmune system in relationship to celiac disease, progress toward a celiac disease treatment can seem slow to patients.

But Kelly, director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a member of the Beyond Celiac board of directors, said important steps forward have been made.

“Ten years ago, there was no pharmaceutical clinical research. All of the clinical research was observational, epidemiological research,” he said. “There was no interventional research in terms of developing new treatments.”

Scientists now have a better understanding of what the study design for a new treatment should look like and what they need to be measuring.

Various potential treatments have moved from preclinical stage to the clinical stage and two are nearing the end of the middle portion of that process, with one expected to go into the final stage of study in next few months.

The Food and Drug Administration requires three phases of clinical trials before it will approve any drug and allow it to be available for patients.

“There has been a lot of progress, but I would say it’s not over until the FDA sings ‘Aye,’ to some agent,” Kelly said, adding that when that happens he expects it will be a huge boost to interest in celiac disease drug development.

“We know a lot about what causes celiac disease…so there are multiple attractive treatment targets for clinical researchers and pharmaceutical companies,” he said. Still, the first drug to treat celiac disease has yet to be developed, and Kelly called current research efforts “pioneering.”

Clinical researchers have difficulty getting federal funding from the National Institutes of Health, which give less money to celiac disease than other less common gastrointestinal disease. In fact, Kelly said the biggest challenges researcher face are “money, then money and money again.”

“It’s great news for pharmaceutical companies to have an agent that might be effective in a chronic disease that may affect one percent of the population,” he said, referring to the number of people in the general population thought to have celiac disease. “The bad news is no one else has done it before. The path to approval is unknown. The benefit may be great, but the risk is great.”

Additionally, Kelly said, patient interest in participating in clinical trials has fallen off, ending what he called the honeymoon period when patients were anxious to get involved in the study of a condition they considered long neglected by science. The importance of patient participation was one of the main themes of last year’s research symposium.

Patients sometimes hesitate to get involved in clinical trials because they fear that study of new treatments will require them to consume some gluten to test whether a drug works. But Kelly said many trials do not include a gluten challenge and instead study the effects of a treatment on those who have ongoing symptoms despite being on a gluten-free diet. This approach has more appeal to the FDA because it reflects a real-world situation versus the contrived scenario created when gluten is purposely given to study participants. The gluten challenge is most often used in the early phases of drug study, Kelly added.

Patient questions

In addition to discussion of their areas of expertise, symposium panelists were asked questions from patients on topics including probiotics, the necessity of the gluten challenge for diagnosis, lack of healing on the gluten-free diet, the connection between the gut and the brain in celiac disease, and the relationship between celiac disease and development of other autoimmune conditions.

Asked if it will one day be possible to diagnose celiac disease in those already on a gluten-free diet without a gluten challenge, Kelly said two companies have developed methods that significantly reduce the length of the time someone would have to eat gluten again.

Instead of six weeks, patients would have to challenge themselves for only two days, he said. However, neither diagnostic tests based on the shorter challenge is available to patients yet.

Regarding probiotics, Leonard recommended naturally occurring probiotics found, for example in yogurt, over those found in supplements and pills. She said that since there are trillions of bacteria in the gut and only about 20 are covered by probiotics on the market she has a difficult time thinking the ones on the market will alter the disease process.

Kelly said he often prescribes probiotics to treat, for example, infections that result from use of antibiotics, but he said these are specific probiotics proven to treat specific conditions. Otherwise, probiotics may be too general to do any good, he said.

“You don’t go into a drug store and say I want drugs,” he added. “In the same way it’s not helpful to say I want a probiotic. You may be taking a probiotic that would work for one thing, but not for the thing that ails you. “

Patients who do not heal on the gluten-free diet often are unknowingly still being exposed to some amount of gluten, something new tests for gluten in stool, urine and food have helped reveal, Kelly said. However, in some adults, long-term damage from celiac disease causes changes to tissue that prevents subsequent healing. Non-responsive celiac disease has also been found in some children. Refractory celiac disease can also be the cause of ongoing symptoms, though this is the most severe form of the disease and is also the rarest.

Leonard said there are several theories about why celiac disease causes neurological symptoms. One is that in the inflammation process some of the inflammatory cells go to the brain. Another is that a particular makeup of the microbiome may be signaling to the brain and causing symptoms.

The link between celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases does not have a clear explanation, Miller said. But he said it is possible that those with one autoimmune disease may have the genetic background that makes them highly susceptible to presenting autoimmune antigens that lead to other conditions.

Alice Bast, CEO of Beyond Celiac, said the symposium was held to give the celiac disease community information about the latest developments in research to enable them to live healthy lives without the burden of worry about gluten exposure and to give them access to researchers to answer patient-submitted questions.

“As part of our work to drive research, we launched a convenient way to make sure the voice of the community is in the research mix,” Bast said. She urged members of the live and online audience to join Go Beyond Celiac, a patient registry and platform, and add their stories to the thousands already collected.

.

Opt-in to stay up-to-date on the latest news.

Yes, I want to advance research No, I'd prefer not to